New Moon Watch: The Envy of Achievement

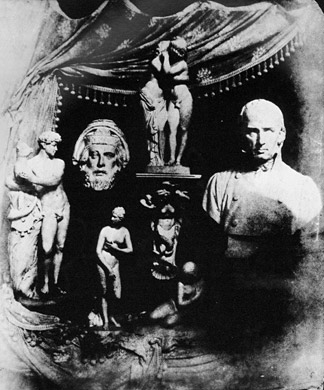

“The Ancients weighed the achievement of an individual by the sum and substance of his actions. Most of Plutarch‘s biographies–for example, of Themistocles, Alcibiades, Pompey, and Antony— are heroic assortments of virtues and vices, clear renderings of the psychological diversity and paradox which seem almost indispensable components of historic greatness.

We moderns, on the other hand, influenced by our religion, qualify all our estimation with a surgical standard of moral purity.

For the ancients, virtue was action, accomplishment, contribution; for us it is an essence so pure and fragile in nature that a beaker of goodness can be ruined by a dram of sin.

Dante makes his beloved teacher, Brunetto Latini, a sufferer in hell, because all his memorable virtues were combined with a single serious vice. Francis Bacon is almost never mentioned as a historical figure without reference to the single act of malfeasance which, deftly exploited by an enemy, ended his political career. The grievous and numerous faults of Winston Churchill are expounded upon interminably by the beneficiaries of the free institutions he fought to save.

And this stubborn altruism, often so extreme as to constitute a conspiracy against nature, extends beyond our histories into our daily lives. Shunning peccadillos, we suffer infamies. Anxious to avoid even appearing to do harm, we lose touch with the necessarily hazardous practice of goodness. We use rectitude to mask our envy of achievement.”