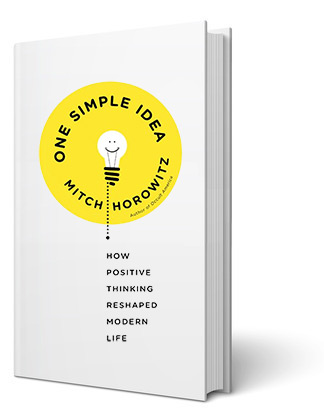

Bright Thoughts: The Mitch Horowitz Interview

In the opening to his new book One Simple Idea: How Positive Thinking Reshaped Modern Life, author Mitch Horowitz recounts his childhood fascination with inspirational wisdom.

For him it all began with a poem that hung on the wall in his big sister’s bedroom. A blacklight poster that included phrases like:

“Forget yesterday. I am where I am. Tell me friend, what can I do today, to be where I want to be tomorrow?â€

When Mitch’s father lost his job and financial conditions in the family took a downward arc, his curiosity about the possibilities of positive thinking grew, leading him to eventually study the writings of Emerson and Talmud. His hope was that his internal attitude and perspective of mind could make a difference.

Horowitz attributes aligning with uplifting thoughts as a remedy that didn’t so much as change his family’s fortunes –- which did gradually improve — but as a practice that helped him “navigate his life. And maybe something more.â€

And it’s that “something more†that Horowitz explores in detail in his meticulously researched book.

As Mitch explains: The idea of “positive thinking†was the product of “a determinedly modern†group of American men and women. Experimenters, sometimes working together and other times in private, who “resolved to determine whether some mental force — divine, psychological or otherwise — exerts an invisible pull on a person’s daily life. Was there, they wondered, a ‘mind-power’ that could be harnessed to manifest outcomes?â€

And let’s get real, isn’t this a question that each of us ponders, secretly, every day of our lives? “Does my thinking have any influence on the outcome of events in my life?”

We tell ourselves: “Yes, of course!” And live our lives with that conviction. But when our head hits the pillow at night are we assured of our certainty? I wonder.

And it was for that reason I looked forward to interviewing Mitch about his new book.

What good is thinking positively? Is it just another disconnect from rationality? A breach we’re taunted about regularly, now that an anti-religious movement has gained traction in popular culture.

More than just the history of the positive thinking movement (which eventually became known as New Thought), Horowitz’s book, in the final chapters, really hunkers down and contemplates (and attempts to understand) the big questions — especially as they relate to the power of volitional thought.

Does it work? How might it work? And what insights do quantum mechanics reveal about thinking and how it might impact reality? (You’ll be amazed when Horowitz reveals these strange secrets!)

I spoke with Mitch last week about these secrets, questions and more after he returned from a recent talk he’d given in Virginia Beach on Edgar Cayce and the positive thinking revolution. Â

And here’s how our conversation flowed:

Frederick Woodruff: Reading One Simple Thought was an adventure that inspired both awe and (a little bit of) envy. Your command of historical facts and your ability to articulate them so colorfully made for a really enjoyable read. I was bummed out when the book ended.

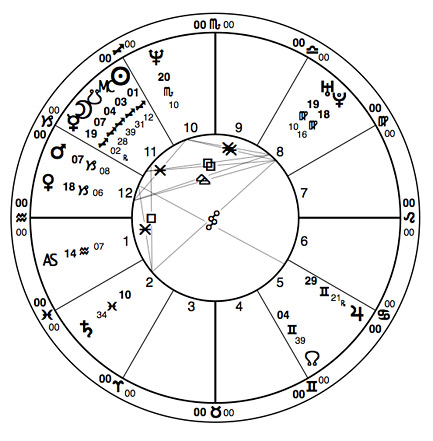

As an astrologer, familiar with your birth chart (which you shared with us in your last interview) I kept thinking — while reading your book — that no other author could have written the book with same spirit of enthusiasm that you delivered. You and the book seemed destined for each other.

Your Sagittarius Sun, Moon and Mercury; Aquarius ascendant and Jupiter in Gemini — that combination is the hallmark a buoyant, optimistic approach to life, shored by a Samurai-like command of language. In other words, it’s a celestial decree that One Simple Idea – a testament to positive thinking — would be part of your destiny.

Would you agree? Did the idea for the book and its composition have a fated feel for you?

Mitch Horowitz: First off, thank you so much. I am optimistic only when I have a purpose in view — and for me this book summoned a deep sense of purpose.

Many of its figures are the forebears and popularizers of American metaphysics — which centers on the principle that thoughts are causative. I believe that they really lived for something, and stood for something — namely, the belief that the metaphysical could bring help in daily life.

They were ardent experimenters, and they wanted to test what they saw as a line of connectivity between thoughts and spiritual experience. They attained an early grasp of the subconscious mind and posited some very workable, practical ideas.

I wanted their story to be told. I also wanted to defend them, since there persists a very poorly examined intellectual assumption that positive thinking is a philosophy for dummies, or just a tragic delusion that distracts us from real social-economic issues. That assumption requires reexamination. So, all of this set me to writing with a deep sense of mission.

•

Frederick: Did your research extend towards Eastern concepts of mind control? And is there any sort of correlation to New Thought in the Eastern spiritual traditions?

Mitch: There are connections, but they have less to do with any direct influence than with an intriguing congruency of ideas across vast stretches of time and geography.

In ancient Hermetic thought, in the decades immediately following Christ, it was believed that an individual, through the right preparation, could commune with nous, or a universal mind, and in so doing experience vastly expanded perception and mental prowess.

There are also certain Vedic ideas that correlate with New Thought. But one must be very careful not to draw hasty connections.

What we call New Thought, or positive thinking, began with the New England mental-healing movement of the early-to-mid nineteenth century. New Thought’s progenitors, especially the Maine clockmaker Phineas P. Quimby, were first dealing with ideas from the occult healer Franz Anton Mesmer.

In the late eighteenth century, Mesmer enthralled Parisians with his theory that all of life is animated by an invisible, etheric fluid called animal magnetism. Mesmer placed patients into trances from which he believed he could manipulate their animal magnetism to bring about healings. What Mesmer demonstrated was not the existence of animal magnetism, but the workings of the suggestive, subconscious mind. And he did so generations before Freud.

News of Mesmer’s trance treatments travelled across the Atlantic in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. One of Mesmer’s earliest proponents was the French hero of the Revolutionary War, the Marquis de Lafayette, who told George Washington about Mesmerism. Washington briefly corresponded with Mesmer.

In the decades immediately ahead, New England experimenters reworked Mesmer’s methods into the early protocols of hypnotism, mental suggestion, and visualization. They believed they were working with spiritual laws. As time passed, however, they edged closer and closer to a modern psychological language.

Now, many of these people, Quimby especially, were self-educated, lived in rural settings, and were not widely read. Even those who were well educated, such as Mary Baker Eddy (who worked with Quimby and later founded Christian Science), had no access to English-language editions of Vedic or Hermetic literature.

In 1841, the year that Ralph Waldo Emerson published his first series of essays, there existed only four copies of the Bhagavad Gita in the United States, mostly in private hands.

The first partial English translation of the Tao Te Ching did not appear until 1838. So, the earliest founders of mental healing had no access to these things. They did, however, have access to the King James Bible, to circuit-riding Mesmerists, to some early translations of Emmanuel Swedenborg, and to their own personal experiments and ideas.

They were extraordinary pioneers. But they were not imbibing deriving ideas from Eastern or Hermetic traditions. What’s remarkable is that ethical and spiritual seekers, separated by vast reaches of time and geography, sometimes independently converge in their ideas, as did a few of these American seekers and their counterparts from the distant East or from late Ancient Egypt.

•

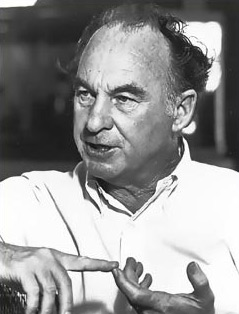

Frederick: Of the various characters you outline in One Simple Idea, Vernon Howard (right) caught my attention in a big way. I sensed that he was on to something that was both practical and of spiritual value for his followers.

You note how he came to a ‘remarkable maturation’ and interrupted his booming ‘how to succeed’ publishing enterprise (riddled with madcap titles like: Your Magic Power to Persuade and Command People) and embraced a ruthless kind of self-scrutiny that I consider a necessity for anyone on a genuine path, and doubly so for someone who presents himself as a teacher.

Many of of his teachings are reminiscent of Gurdjieff’s: People are asleep to their true nature and identified with values that distract from any genuine self-realization. And more cogently: People live with a false, ‘acquired’ self that dominates their lives; a condition that precludes self-awareness.

But I’m curious. Did you have a similar sense about Howard, appearing when he did on the New Thought timeline? Did you suspect that when he found a solution to his personal identity crisis he’d also confronted, and then attempted to correct, what I call ‘the New Age Shadow’: The spiritual materialism that haunts much of the New Thought movement?

Mitch: Yes, I think Vernon began in the New Thought tradition. His early books, from the 1950s and early 1960s, show an instinct (held by many American spiritual experimenters) that the mind could bring us to the threshold of spiritual experience — but his early works were oriented toward practical self-help and motivational business ideas.

Vernon underwent a profound spiritual awakening in mid-to-late sixties, which changed everything for him. He came to feel that we are all living from corrupt values and that there is a truer, eternal existence that we can enter if we suspend our conditioned ideas of self, success, and ambitions. “The kingdom of heaven is the space between two thoughts,†he said. He believed that by opening ourselves to the current of an eternal spiritual energy, or God, we could become vessels of this higher truth.

Gurdjieff’s language can certainly be found in Vernon’s later books. Yet Vernon resisted being associated with any thought school or antecedent. He simply said that his ideas were from the New Testament, Taoism, and various wisdom traditions. Though he specifically cites Gurdjieff, Ouspensky, Krishnamurti, and Ralph Waldo Emerson, among others.

I think that Vernon, who died in 1992, was one of the most practical and unclassifiable spiritual philosophers our nation has ever produced.

•

Frederick: I really enjoyed reading about the history of Alcoholics Anonymous and how AA (and it’s twelve-steps) became the most constructive and far-reaching development of the New Thought movement.

Today, when HMOs would rather medicate than pay for the kind of sustained self-inquiry that ongoing therapy provides, a program like AA or Twelve-Step is a veritable godsend.

But what’s interesting to me, and I’m curious to hear your thoughts on this Mitch, is what I’m told dissuades some individuals who might benefit from the program; namely the step that acknowledges one’s relationship to a “higher power.â€

I know this is very broad question; one that philosophers ponder endlessly, but why are some people predisposed to embrace this spiritual requirement while others cannot?

Mitch: Well, AA, at its inception, was really very liberal about the Higher Power idea. Bill Wilson was ardently committed to avoiding any kind of sectarianism in AA. He didn’t want to form a dogma. And he realized that many alcoholics were agnostics, or were uncomfortable with religious language.

A journalist named Jack Alexander, who was lifelong friends with Bill, wrote a very influential piece about AA in 1941 in the Saturday Evening Post.

In this article, Jack went even further than the Big Book in emphasizing AA’s religious openness. One passage bears quoting: “Any concept of the Higher Power is acceptable. A skeptic or agnostic may choose to think of his Inner Self, the miracle of growth, a tree, man’s wonderment at the physical universe, the structure of the atom, or mere mathematical infinity.â€

I’m sure Bill would have agreed with this, as he and Jack were confidants. In fact, Bill may have seen Jack as a kind of ambassador of his ideas, and as someone who was able to go further in espousing the openness of the Higher Power concept than Bill felt at liberty to do in the Book Big, which was written on the basis of consensus.

It may have been similar to how Johnny Carson used to invite Gore Vidal on The Tonight Show to utter radical political views, which Johnny agreed with, but was unable to express in front of his sponsors.

I should add that Bill also emphasized AA’s debt to William James and Carl Jung. Bill had many sources of influence but he seemed to emphasize these ties to Jung and James, probably because he wanted to stress AA’s openness and to shed certain ghosts of the past, especially involving another of his early influences, the Oxford Group.

The Oxford Group was a brilliant and innovative self-help evangelical fellowship. But Bill ran into conflict there. He felt that the Oxford Group’s internal culture was sectarian, and he winced at how Oxford’s leader espoused ultra-rightwing political views — which is a long and discursive topic. Bill and his wife, Lois (whose family was active in the liberal Swedenborgian church), grow uncomfortable within the Oxford Group. So, Bill later took pains to note the contribution of Jung and James to underscore AA’s principle of religious flexibility and non-sectarianism.

It was Jung, by the way, who devised the Latin phrase “spiritus contra spiritum,†which means, roughly, Higher Spirit over lower spirits. Each time I sign a copy of One Simple Idea, I put that on the signature page.

•

Frederick: After traversing the entire history of the New Thought, New Age and Magical Thinking movement, as you organized it for the reader — there was for me, in finishing the book, an aftereffect of having revisited many of the stages that comprised my efforts, over the years, on a spiritual path. Belief systems and practices that I’d explored, engaged and then eventually left behind.

For this reason I recommend your book to peers in my spiritual school. Many of us are now situated at a very paradoxical juncture; confronting the age-old philosophical question of doing versus being.

Pondering the question of volition (and if it even exists) and also how to function in life when one begins to live, more or less consistently, in the non-dual condition. Which I’m sure you are familiar with in your own quest.

Always there is a fascinating toggle between what I’d describe as, for the sake of brevity, personal will versus universal will.

Can you talk about the experience of having completed the book and how the insights you present to us at the end (which to me were the book’s most insightful inquiries) mirror your own spiritual development and how it is situated presently?

Mitch:Â That is a question that I wrestle with every day: Am I surrendering myself to the will of a higher power or am I simply pursing my own self-conception of what life ought to look like?

Or, coming at this question in a different way, can I somehow direct my personal aims through the help of natural law or higher ethics? Almost every spiritual seeker experiences some kind of friction between the question of self-development and self-pursuit. We exist within the tug of these currents: surrender versus attainment. We cannot hide from this division.

A further complexity is that different parts of us want different things. One part of me wants truth; another wants success. Can these things be merged? Or perhaps there isn’t any real division.

In any case, we should try to be blunt with ourselves about our motives and aims on the spiritual path. It’s tricky because we may tell ourselves, and others, that we’re feeding the soul when we’re really attempting to gain the world. Again, some would argue that there’s no division between material development and spiritual growth, and in some respects I believe that’s true. But we have to fall to knees in front of this question. I’m not sure that it ever goes away or gets fully resolved.

•

Frederick: I’d like to talk about the pervasive impact of the New Thought movement (especially its gospel of prosperity) and how that became the imaginative fuel for the American Dream.

“I can succeed, I can be prosperous, regardless my class, history or lack of opportunities.â€

This is an aphorism that’s echoed — in neon — in the USA’s natal horoscope, with its Sagittarius ascendant and the chart’s ruler, Jupiter, conjunct the Sun.

What are your thoughts on the correlation: New Thought’s gospel of prosperity and how that supports the American Dream?

Mitch: New Thought , which came into use as a term in the 1890s, tapped into the American ideal that every individual could forge his or her own identity, own sense of self, and personal ideal of success. New Thought represented a radically individualistic outlook, and it was completely unfettered from religious orthodoxy.

Hence, artists, radicals, and avant guard figures, formed New Thought’s earliest culture. These included the black nationalist Marcus Garvey, the suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and the socialist activist Wallace D. Wattles, who is most famous for writing The Science of Getting Rich, which he saw as a manual for the emancipation of working people, women, and minorities.

It was only later, in the 1920s, that New Thought and the prosperity gospel moved out of the orbit of the Progressive Era and adopted a more rah-rah business tone.

•

Frederick: Last week when I posted on Facebook about our interview, and asked folks to submit questions for you, what surprised me was that everyone who responded shared a similar version of the same question:

“What does Mitch think of Barbara Ehrenreich’s book: Bright-Sided: HowPositive Thinking Has Undermined America?â€Â For those not familiar with the book, I’ll pilfer from the book’s sleeve:

Ehrenreich “…confronts the false promises of positive thinking and shows its reach into every corner of American life, from Evangelical megachurches to the medical establishment, and, worst of all, to the business community, where the refusal to consider negative outcomes–like mortgage defaults–contributed directly to the current economic disaster…Ehrenreich exposes the downside of positive thinking: personal self-blame and national denial.â€

In her book, Ehrenreich shares her experience with breast cancer and how, from the support groups she consulted, she was instructed to see the disease as ‘a gift’ and to think only positive thoughts about the disease — to ensure her recovery.

She also researches and catalogs the positive thinking movement’s historical timeline. But really saves her ire for contemporary versions of New Thought, like the Oprah-sanctioned phenomenon The Secret.

As she said in an interview recently:

Positive thinking “really began to take off in a very big way in about the ’80s and ’90s, because the corporate world got very interested in it, got interested in it during the age of downsizing, because it was a way to say to the person who was losing his or her job: “This is in your mind. You know, you can overcome this. If something bad has happened to you, that must mean you have a bad attitude. And now, if you want everything to be alright, just focus your thoughts in this new positive way, and you’ll be OK.â€

She wrapped that comment up with:

“I can’t tell you how many times I have read people who have lost their jobs in this recession in the newspaper saying, “But I’m trying so hard to be positive.†Well, maybe there’s no reason to be positive. Maybe you should be angry, you know? I mean, there is a place for that in the world.â€

How do her ideas sit with you? Is it possible that New Thought is ready for a kind of overhaul, or reality check? And what might that be?

Mitch: I agree with her up to a point. The problem I have with her analysis is that, while she rightly indicts the grosser aspects of positive thinking — and I make some of the same arguments — she never considers how or whether the movement has also brought meaning to people’s lives.

She spends very little time on the history of the movement, other than to note offhandedly that its history includes some colorful figures. She doesn’t realize what a tremendous corrective New Thought provided to religious conformity in the first half of the twentieth century. Nor does she understand positive thinking’s radical roots. And that matters.

I know Barbara from my youth when we were both active in the Democratic Socialists of America, the organization founded by the American radical and social thinker Michael Harrington, who died in 1989. People would always say that Mike was an optimist, and in his tone and persona he did, in fact, bring tremendous energy to that movement. Barbara, and any American radical, knows too well the experience of hearing critics caricature the term “democratic socialism,†and make it seem like its advocates are compatriots of Pol Pot, rather than deeply searching people who are seeking humane methods ways of governance, and whose ideas, historically, are deeply democratic.

Yet that critical approach, where only the broadest brushes are used, is exactly how Barbara treats the positive-thinking tradition.

Now, she’s right that it is tragic to hear jobless people speak of how they struggle to remain positive; and, likewise, I agree that many of people have every reason to feel angry toward our lopsided and dice-loaded economy. There’s no question about that.

But Barbara portrays the movement’s grotesque excesses while overlooking both its roots and the depth of meaning and the sense of realistic self-belief that the best expressions of mind-power metaphysics can bring to people.

I did not publish my first books until I was well into mid-life — I am now 48 years old — and, believe me, if I lived at another time, or in another place, where there was no literature or philosophy of self-realization, I doubt that aim would have been reached.

My mother-in-law, Theresa Orr, grew up in Waltham, Massachusetts, as the daughter of an Italian immigrant barber, and she recently retired as an associate dean of Harvard Medical School. Terri achieved all that she did while also raising two daughters, one of whom is my wife, as a single divorced parent. She devoured positive-thinking literature, which she credits with opening her to a sense of possibilities. These stories are part of the panorama, too.

And, socially speaking, if we want to assemble a radical, democratic political movement, we have to sound more like Michael Harrington — who was defiantly optimistic about building a working-people’s movement — rather than rely upon dreary tones of indictment that are supposed to be “realistic.â€

I say, learn lessons from the lives of Wallace D. Wattles, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Marcus Garvey, who were ardently non-conformist and radical, but who believed in, and venerated, human possibility. They understood how to channel their anger at oppressive social systems, but they also believed in the higher dimensions of the individual.

•

Frederick: Let’s shift things up and end on a different frequency here.

In the opening to your book you state that you like “rejected stones,†implying that some of the doctrines of the New Thought movement were just that.

I’m curious as to how your ‘rock collection’ is presently configured? What new outcasts have caught your eye in the contemporary metaphysical landscape?

Mitch: I recently returned to reading A Course in Miracles, which I find a deeply affecting and rich text.

I’ve renewed my familiarity with Alcoholics Anonymous, which, in actuality, is really an application of the spiritual ideas of William James, particularly James’s idea of a “conversion experience.â€

I’m always reading Vernon Howard, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Scripture, particularly the Gospels. I believe deeply in the American spiritual mission: which is to posit the spiritual search as a quest for practical, daily help; we need a spiritual and ethical philosophy that is open to everyone, and that can be experienced and practiced in the daily hours of life.

We need a spirituality that goes with us into airports, on highways, at family dinner tables, and in workplaces. That, for example, is why I love the emphasis on forgiveness in A Course in Miracles, though those teachings run much deeper than one at first suspects. I am continually touched by, and attracted to, popular expressions of spirituality, which can reach people in crisis.

I think the spiritual culture today is burdened by a false distinction between what is considered “serious†and what is “unserious.†For me the question is: Does it work? There is no efficacy in a religious system that does not result in a person who is better for others to live with.

•

Frederick: You have a nearly exact Uranus Pluto conjunction in your birth chart. I thought it was uncanny, though not surprising, that right when Uranus Pluto moved into their current 90 degree square, One Simple Idea was published.

Astrologically, we can read that sequence like this: What was promised at the conjunction in 1965 — the beginning of the counter culture movement — has now reached a point of enactment; an embodiment of the ideals promulgated in the mid-60s.

Your book offers a historical summation of the very ideas that helped foment the radical shifts of consciousness that marked the mid-to-late 60s and the occult revival that followed.

As that occult revival lost its teeth, what was left in its wake is the contemporary New Age mindset.

So, Mitch, as an ambassador for that seed moment in the 60s, are we ready for another occult revival, as you alluded when I spoke with you last year for comments about the ongoing Uranus Pluto square?

Mitch: It’s funny, but this morning a British journalist asked me that very question.

Honestly, I do not see an occult or mystical revival on the horizon. I do see New Age ideas being continually embraced by mainstream people, who understandably resist placing labels on themselves.

But since that question is in the air — is there a New Age revival? — perhaps it taps into something.

I see one indictor pointing to the possibility of a “new New Age†— and that is the near-total intellectual triumph of materialism today. A triumph, of any kind, usually brings a reverse current.

Parapsychology, as a field, is in tatters; the brightest and wittiest voices on television, such as Bill Maher and Rachel Maddow, think religion is something of a joke; many of the most popular philosophers and social commentators, such as Richard Dawkins or the recently deceased Christopher Hitchens, write from an atheistic perspective; the digital revolution, along with concurrent revolutions in genetic mapping, have directed the minds of many young people to look to bytes, binary codes, and genomes for the mysteries of life, not to consider questions of the ineffable; and, finally, there is no witty, media savvy cohort today who can defend religious experience, while there are lots of bitingly effective, highly visible materialist spokespeople.

Those of us who care about the mystical have lost the public debate, insofar as we care to participate in it. But that very loss may signal the inevitability of a cultural turnaround, just as tides ebb and flow. That, perhaps, is why we feel an occult or mystical revival may be underway.

•

Frederick:Â Excuse this loopy segue, but talk about your great collection of rock band t-shirts. Are you an avid collector?

And do you know of any musicians that employed New Thought principles in his or her career? Or perhaps even less savory techniques from the occult world. (I guess this is your cue to mention Jim Morrison, maybe?) :o)

Mitch: I’m not really a collector but I do love rock, and I finally just started wearing what I’m comfortable in every day. I grew up on The Who, the Clash, the Doors, and the Dead Kennedys. Many of these musicians experimented with mysticism, a topic handled really beautifully by my friend Peter Bebergal in his new book Season of the Witch: How the Occult Saved Rock and Roll. It comes out in October.

Elvis, too, was a real New Ager and his library was filled with Manly P. Hall, Ernest Holmes, Madame Blavatsky, and a catalogue of modern metaphysical figures.

I actually had tickets to see Elvis at Nassau Coliseum on Long Island when I was twelve years old — and he died just five days before the concert. That’s what it means to be an Elvis fan — you get your heart broken. But realizing that Elvis loved some of the people and ideas that I write about has been a kind of homecoming for me.

•

Frederick: And finally, a question most Sagittarians appreciate: What’s next for Mitch Horowitz?

Mitch: I really don’t know! I’ve been writing about a new wave of violence going on worldwide against witches, ironically enough, in the twenty-first century. I’m trying to bring attention to that, to find ways of curbing it, and specifically to call attention to a case in Saudi Arabia where the government has imprisoned a Lebanese man named Ali Hussain Sibat, whose “crime†was hosting a psychic hotline television show in Lebanon.

The Saudis seized Sibat while he was on pilgrimage to Medina and sentenced him to death by beheading on charges of sorcery. The death sentence was set aside, thank God, but he remains in prison. I am trying to bring notice to his case. If anyone is interested, they can email me and I will give them the Saudi king’s mailing address if they want to write in protest.

As far as new books, I haven’t found a topic yet. I need something that I am totally impassioned about, that gives me a sense of purpose. Until that comes I need to be very patient. I’m doing a lot of narrating and television work, and that’s important to me, since it revives interests that I had as a teenager. That’s really been my whole life – rediscovering the things that made me feel hopeful and driven when I was a kid.

•

Opening photo of Mitch Horowitz by Shannon Taggart © 2014